-

Postów

1 409 -

Dołączył

-

Ostatnia wizyta

Treść opublikowana przez Andrew Alexandre Owie

-

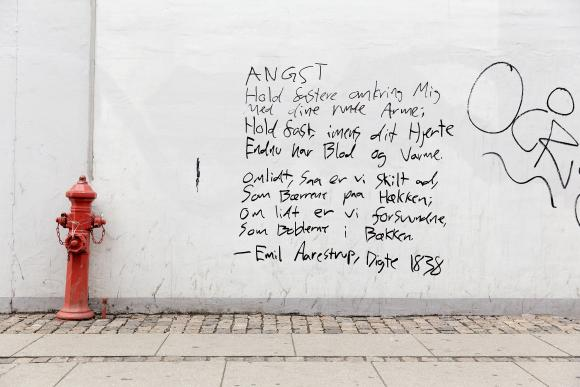

Pastime Paradise*) ŽAL SE ODKLÁDÁ GRIEF HAS BEEN POSTPONED SMUTEK JEST ODKŁADANY Žal se odkládá Grief is being postponed (or: Grief has been postponed) Smutek jest odkładany. Sung & danced by Czech pop star Jiří Korn. Śpiewane i tańczone przez czeską pop gwiazdę Jiří Korna. Před týdnem, kvůli jedné madmasel, v prachbídném stavu jsem se nacházel, zničen zradou, jed jsem chyt, vzhůru bradou chtěl jsem být. A week ago, Due to one of my girlfriends [var.: ...one mademoiselle], I felt low, I had never felt such angst [var.: ...such pain], Cheated, sucked it!, Got some bane To kick the bucket, Since life's in vain. Tydzień temu, Z powodu jednej madmazelki, Czułem się źle, Nigdy nie czułem takiego smutku, Ona mnie zdradziła, do diaska! Zdobyłem truciznę, Więc niedługo wyniese mnie Nogami do przodu. Jenže tentýž den, už jen po krk nad vodou, skvost všech žen, potkal jsem vám náhodou, řek jsem: jedem, bude bál. K čertu s jedem, žijme dál. The same day, Just a shadow before death (var.: Just one step away from death), On my way I met another belle of belles. I said: "Gorgeous, Let's have the ball [var.: prom]! To hell the poisons, Life goes on!" Tego samego dnia, O krok od śmierci, Spotkałem przypadkiem kolejną Piękność nad Pięknościami. [dosł. spotkał cię przypadkiem, klejnot wszystkich kobiet] Powiedziałem: "Skarbie, Chodźmy na bal! Do diabła z trucizną, Żyjmy dalej!" CHORUS Žal se odkládá, změna termínu, Útěk ze stínu to jsem zvlád. Žal se odkládá pro můj nezájem. Stojím před rájem a jsem rád! Grief has been postponed, Time has re-appeared, Dark has disappeared, I've done that. Grief has been postponed, I avert my eyes, I'm in Paradise, I am glad. Smutek jest odkładany, Zmiana czasu i daty, Cienia uciekli, Poradzęłem sobie z tym. Smutek jest odkładany, odwracam oczy [od niego] (dosł. za mój brak zainteresowania) jestem jak w raju, (dosł. Stoję przed rajem), I cieszę się. Před včírem též jsem nejlíp nedopad, kvartýrem se mi přehnal vodopád, co si počít, vážení, z římsy skočit okenní? Ereyesterday I had got again no luck. At my place, There happened a big flood. What would YOU do, My beloved? Jump outta window, Aren't I right? Onegdaj Znowu nie miałem szczęścia. U mnie [w mieszkaniu] Zdarzyła się wielka powódź. Co zrobicie, Moi najdroższy? Wybiegniecie przez okno, Prawda? Jenže koukám vám na náš dvorek maličký, zrovna tam kluci hráli kuličky, tak k nim cvalem běžím blíž. Nad svým žalem dělám kříž! But I stared Into our small yard. Kids made there Their pies of sand and mud. I rushed to kids Like on a horse, And o'er my grief I placed the cross! Ale zerknąłem za okno Do naszego małego podwórka, Tam w piaskownice Małe dzieci robili ciasteczki. Ruszył galopem W ich stronę Na moim smutkie Umieściłem krzyż! [położyłem mu koniec] CHORUS *** HOW GOOD IT'D BEEN! JAK DOBRE TO JUŻ BYŁO! Brigitta Nass (East Germany), Jiří Korn (Czech Republic) and Fernsehballett (TV Ballet) Brigitta Nass (Niemcy Wschodnie), Jiří Korn (Czechy) i Fernsehballett (Niemiecki Balet Telewizji) The Fernsehballet videos above and beneath belong to the `Ein Kessel Buntes` (`A Many-Coloured Kettle`) epoch of the 70-80s of the 20 c. Wideo z baletu Fernsehballet powyżej i poniżej z epoki "Ein Kessel Buntes" ("Kocioł wielobarwny") z lat 70-80 XX wieku. Martina & Ferenc Salmayer That time the chief choreographers of the famous East Germany variety show ballet were Hungarian dancers and balletmasters Ferenc Istvan Salmayer, his wife Martina and Emöke Pöstenyi. W tym czasie głównymi choreografami słynnego baletu wschodnioniemieckiego byli węgierscy tancerze i baletmistrzowie Ferenc Istvan Salmayer, jego żona Martina i pani Emöke Pöstenyi. Choreographer Emöke Pöstenyi Mr. Salmayer was an artistic leader of the ballet company. In the 90s he gave way to the next generation of the Fernsehballet soloists and choreographers like Ophelia Vilarova, André Höhl, Cristina Kochmann, Maik Damboldt, and Carsten Rietschel. Choreograf Emöke Pöstenyi Pan Salmayer był kierownikiem artystycznym zespołu baletowego. W latach 90. ustąpił miejsca kolejnemu pokoleniu solistów i choreografów Fernsehballeta, takich jak Ofelia Wiłarowa, André Höhl, Cristina Kochmann, Maik Damboldt, Carsten Rietschel. Hi, Mister Sandman! Jiří Korn & Fernsehballett (TV Ballet), East Germany Cześć, panie Piaskunie! Jiří Korn & Fernsehballett (Balet Telewizyjny), NRD Then came the time of quasi-Broadway shows in Germany, and German and Czech artistes started singing in English. A cultural Cargocult! Potem przyszedł czas na quasi-broadwayowskie przedstawienia w Niemczech, a niemieccy i czescy artyści zaczęli śpiewać po angielsku. Kulturalny Cargocult! The Czech stars were the regular guests of the East Germany variety shows in the 70-80s. My fave musician and dancer Jiří Korn commanded perfect German and moved very gracefully, while manoeuvring among the half-naked dancing girls. How good it'd been! Czeskie gwiazdy były stałymi gośćmi wschodnioniemieckich pokazów odmian w latach 70-80. Mój ulubiony muzyk i tancerz Jiří Korn władał perfekcyjnym niemieckim i poruszał się bardzo zgrabnie, manewrując wśród półnagich tancerek. Jak dobrze to już było! Nostalgia! (Please, do not think that I`m 90-year old grand-daddy! Simply, I value the true things of all places and times!). Nostalgia! (Proszę nie myślcie, że jestem 90-letnim dziadkiem! Po prostu cenię prawdziwe rzeczy wszystkich miejsc i czasów!). (Slavic/Słowiański Michael Czechson). *** Strictly speaking, choreography is the most important art for me. Ściśle mówiąc, to choreografia jest dla mnie najważniejszą sztuką. Anna Bagmet & Andrei Glushchenko-Molchanov dancing in the `N.Y. Streets`. Andrei`s choreography. Of course, a rehearsal of a woman`s dance being shown by the choreography himself. See how gracefully this giant (1 metre 80 cm tall, 80 kg) with a bodybuild of a three-chamber fridge moves! Anna Bagmet i Andrzej Gluszczenko-Mołcianow tańczą w "N.Y. Streets”. Choreografia przez Andrieja. Oczywiście próba tańca kobiecego pokazana przez samego choreografa. Zobaczcie, z jaką gracją porusza się ten olbrzym (1 metr 80 cm wzrostu, 80 kg wagi) o budowie trzykomorowej lodówki! French motion picture Le grand restaurant (1966) – Louis de Funès and Russian Cossack Dance. Francuski film Le grand restaurant (1966) – Louis de Funès i rosyjski taniec kozacki. The choreographer of the Grand Restaurant (1966) was the French actress and screen-writer Colette Brosset (Brossé ) who was a classical ballerina in her young years. She composed the dance to music by Jean Marion. Choreografem w filmie "Grand Restaurant" (1966) była francuska aktorka i scenarzystka Colette Brosset (Brossé), która w młodości była klasyczną baletnicą. Skomponowała taniec do muzyki Jeana Mariona. -------------------- *) Play on words: Pastime Fun time paradise Raj rozrywkowiego czasu Past Times A paradise of bygone times Raj minionych czasów

-

THE FUGITIVE ZBIEG

Andrew Alexandre Owie odpowiedział(a) na Andrew Alexandre Owie utwór w Wiersze gotowe - publikuj swoje utwory

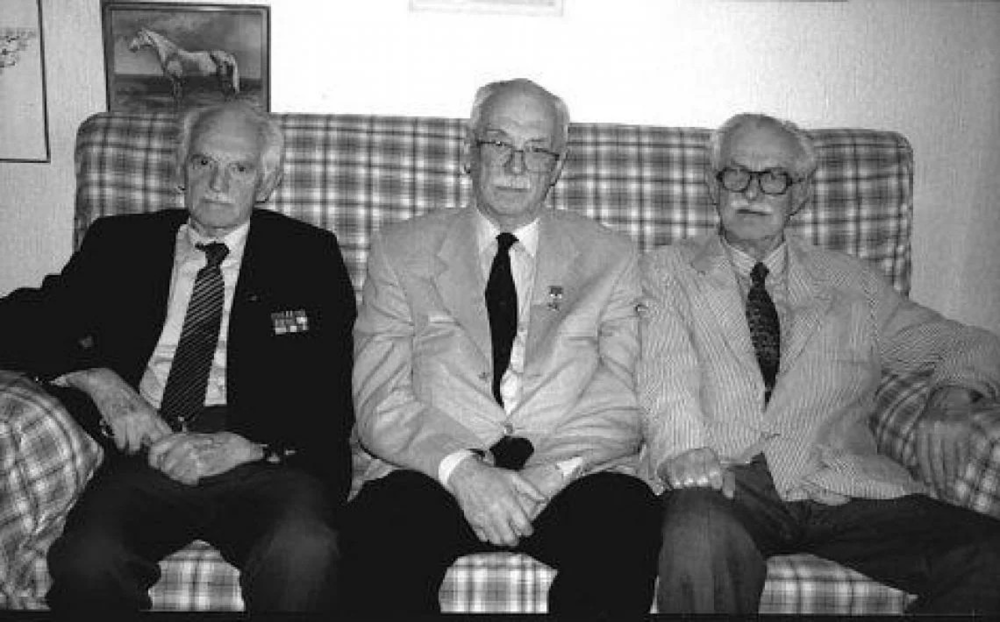

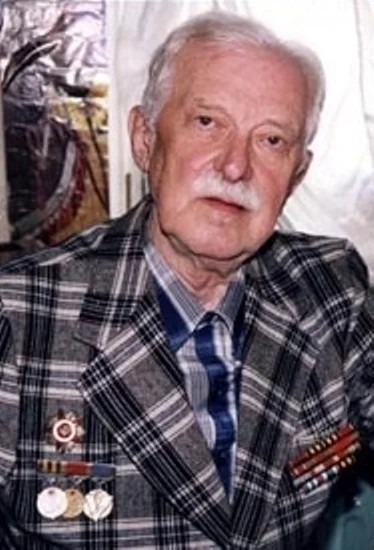

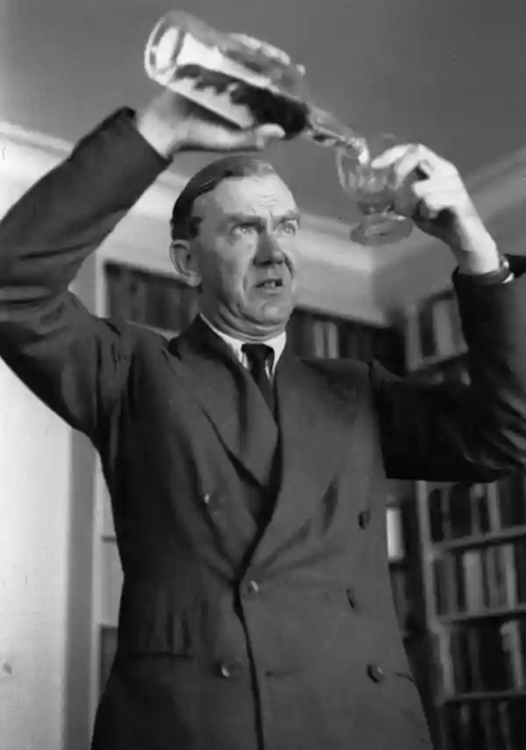

A German prisoner of war taught the German language in our school. We understood what he was saying neither in German nor in Russian. He drank a lot. He called us "durrrraks" [fools] with a rolling, guttural sound of "r". One day the Headmistress entered our classroom and asked if the teacher was drinking? We unanimously replied "No!" After she'd left, our German teacher turned back to the window and burst out crying. W naszej szkole uczył niemieckiego jeniec wojenny. Nie rozumieliśmy co mówił ani po niemiecku, ani po rosyjsku. Pił dużo. Nazywał nas "durrrrakami" [durniami] z wibrującą, gardłową "r". Pewnego dnia do klasy weszła pani dyrektorka i zapytała, czy nauczyciel pije? Jednogłośnie odpowiedzieliśmy "Nie!" Wyszła, a nasz, nauczyciel niemieckiego odwrócił się do okna i zapłakał. -

THE FUGITIVE ZBIEG

Andrew Alexandre Owie odpowiedział(a) na Andrew Alexandre Owie utwór w Wiersze gotowe - publikuj swoje utwory

The "architecture" of what I've been writing for now, what I've been written so far above suspiciously resembles... a symphony. A combination of non-fiction and war pulp-fiction with the psychological prose and poetry, a free-flowing associative jam with a key, common cross-cutting theme. "Architektura" tego, co do tej pory pisałem, to, co napisałem do tej pory powyżej, podejrzanie przypomina... symfonię. Połączenie literatury faktu i wojennej pulp fiction z psychologiczną prozą i poezją, swobodny, skojarzeniowy "plyw" z kluczowym, wspólnym, wszystko łączącym tematem. -

THE FUGITIVE ZBIEG

Andrew Alexandre Owie odpowiedział(a) na Andrew Alexandre Owie utwór w Wiersze gotowe - publikuj swoje utwory

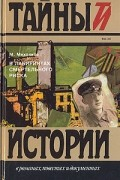

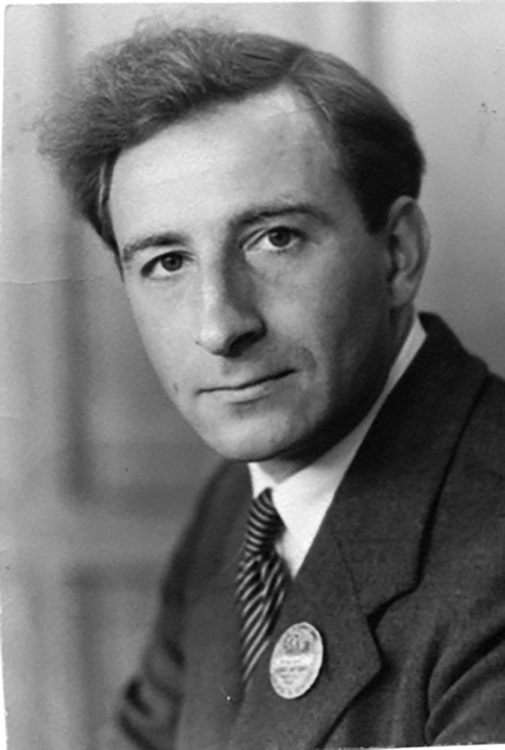

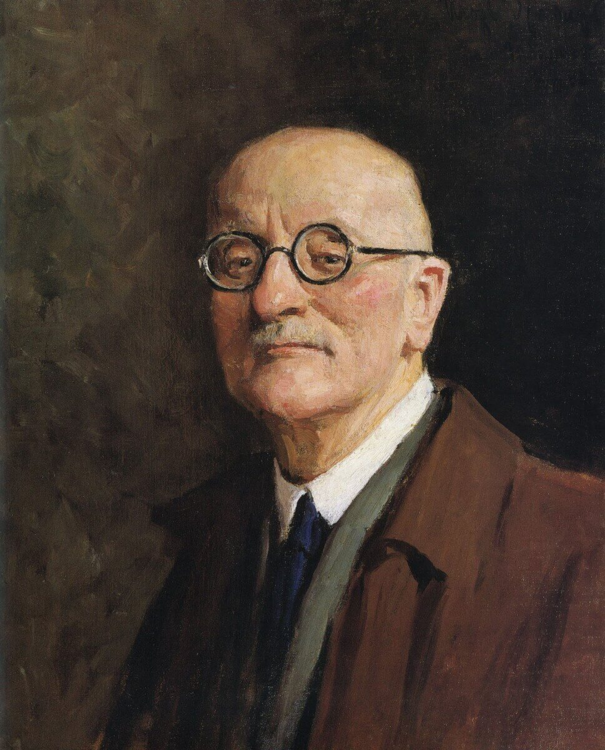

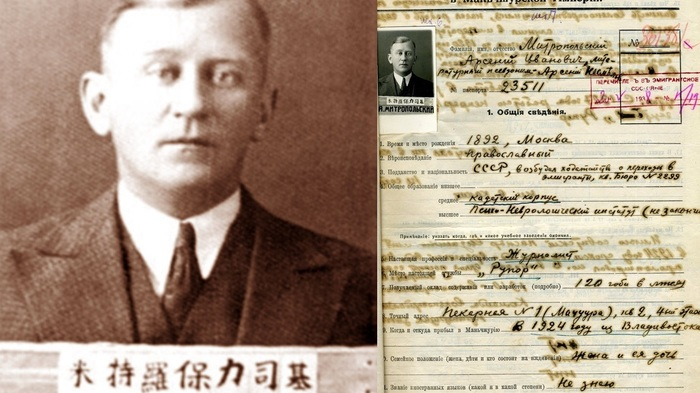

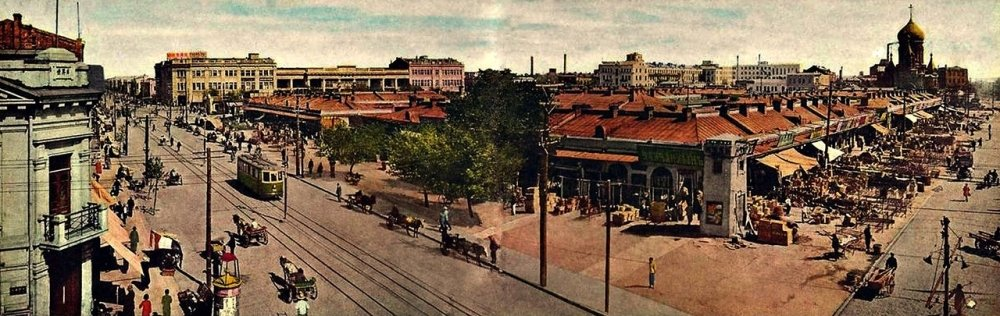

Admiral Kolchak: "Do not touch the artistes, prostitutes and cabmen. They serve any government". Admirał Kołczak: "Nie dotykajcie artystów, prostytutek i woźniców. Służą każdemu rządowi". Adm. Kolchak in Vladivostok in 1918. Adm. Kołczak we Władywostoku w 1918 r. Admiral Kolchak, naval commander, polar explorer, the only member of the highest military caste who opposed the abdication of Nicholas II. Admirał Kołczak, dowódca marynarki wojennej, polarnik, jedyny członek najwyższej kasty wojskowej, który sprzeciwił się abdykacji Mikołaja II. Adm. Kolchak in Vladivostok in 1919. Adm. Kołczak we Władywostoku w 1919 r. During the Civil war, the Supreme Ruler of Siberia and the Far East, "Omsk Ruler", issued to the Bolsheviks by General Jeannin, the head of the French military mission, in conspiracy with the Czechoslovak legionnaires. W czasie wojny domowej Najwyższy Władca Syberii i Dalekiego Wschodu "Omski wojewoda", wydany bolszewikom przez generała Jeannina, szefa francuskiej misji wojskowej w konspiracji z czechosłowackimi legionistami. General Pierre Maurice Janin -

THE FUGITIVE ZBIEG

Andrew Alexandre Owie odpowiedział(a) na Andrew Alexandre Owie utwór w Wiersze gotowe - publikuj swoje utwory

MOST LIKE HIS UNCLE JAK JEGO STRYJ Fim director Stanislav Govorukhin: I remember how we were sitting [with Vladimir Vysotsky] in his flat's kitchen and drank tea when dropped in Nikita Mikhalkov who lived on the floor above. He had visited Tehran, and told us about the Royal couple, the Shah and his spouse. All sorts of the fantastic things. When he left and Volodya closed the door after him, he said: "Look at that dog, how talented he is! He told us a pack of lies, but how interesting! Learn it from him!" Reżyser Stanislav Govorukhin: Pamiętam, jak siedzieliśmy [z Władimirem Wysockim] w jego kuchni i pili herbatę. Przyszedł Nikita Michałkow, który mieszkał piętro wyżej. Właśnie przyjechał z Teheranu. Mówiłem o Szah i jego i jego małżonkie wszelkiego rodzaju fantastyczne rzeczy. Potem wyszedł, Wołodia zamknął drzwi i powiedział: "Spójrz, jaki ten pes jest utalentowany! Nakłamał, co ślina na język przyniosła, ale to takie ciekawe! Naucz się tego!" The King of Kings Shahin Shah Król Królów Szahin Szach -

THE FUGITIVE ZBIEG

Andrew Alexandre Owie opublikował(a) utwór w Wiersze gotowe - publikuj swoje utwory